When [Erich Styger] recently got featured on Hackaday with his meta-clock project, he probably was not expecting to get featured again so soon, this time regarding a copyright claim on the ‘meta-clock’ design. This particular case ended with [Erich] removing the original blog article and associated PCB design files, leaving just the summaries, such as the original Hackaday article on the project.

Obviously, this raises the question of whether any of this is correct; if one sees a clock design, or other mechanisms that appeals and tries to replicate its looks and functioning in some fashion, is this automatically a breach of copyright? In the case of [Erich]’s project, one could argue that at first glance both devices look remarkably similar. One might also argue that this is rather unavoidable, considering the uncomplicated design of the original.

Not copyright, but patent law

An inherent property of copyright law in most jurisdictions is that the act of creating a work automatically grants one the copyright to that work. In most jurisdictions (e.g. the EU), signing away one’s copyright is even forbidden by law. Not so with patent law. Here we have two distinct forms, one being patents as we all know and love them, for the patenting of ideas and inventions. The other form concerns itself with what a product looks like: its design.

In the US this is referred to as a ‘design patent‘, while elsewhere it is referred to as a ‘registered design’, which effectively comes down to the same thing. It means that one can patent for example the shape of a Coca-Cola bottle, or in the case of the folk at Humans Since 1982 (‘HS1982’) the look of their meta-clocks, in not one, but two EU registered designs.

Comparative analysis

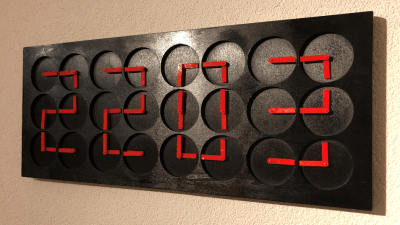

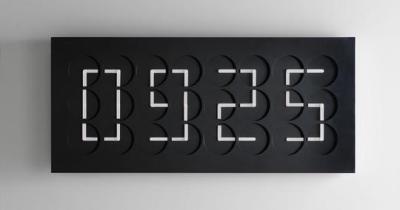

We can compare the two designs side by side to see how similar they are.

The top design is [Erich]’s, while the lower design is HS1982’s clock (black version). Both have the same 8×3 hole pattern, similar color scheme, and so on. That the HS1982’s version is in a mineral composite housing and [Erich]’s in a wooden enclosure is hereby not relevant as it does not change the design. To the casual observer it might indeed appear as if both follow the same design.

The top design is [Erich]’s, while the lower design is HS1982’s clock (black version). Both have the same 8×3 hole pattern, similar color scheme, and so on. That the HS1982’s version is in a mineral composite housing and [Erich]’s in a wooden enclosure is hereby not relevant as it does not change the design. To the casual observer it might indeed appear as if both follow the same design.

Since design registrations are meant to deter companies from for example selling their own soft drink in a bottle that looks exactly like a Coca-Cola one, down to the label design, it makes sense that HS1982 came down on [Erich] and others with similar clock designs like the proverbial sack of bricks.

Naturally, the next question which one should ask here is whether it makes any difference that this was a freely available, open project. Meaning that there was no intention to sell such clocks, or even provide all of the necessary information to assemble a clock from scratch, including the software.

Consistency is key

Although with patents and design registrations there is no need to actively pursue infringement cases to keep the patent as is the case with trademarks, it’s likely that to HS1982 there was no question of tolerating any form of infringement. Their audience appears to be those interested in exclusive art pieces, with the device described by them as ‘both a kinetic sculpture and a functioning clock’.

The manufacturing costs of a single ClockClock24 device is unlikely to be even half the asking price of $6,000 to $10,700, even taking into the account that each version is a limited edition. Yet this asking price remains only ‘legitimate’ if the product remains as exclusive as possible. This provides HS1982 with enough incentive to actively seek out and destroy any similar products. In the end we are talking about sculptures, i.e. art, here.

This isn’t just like one smartphone manufacturer accusing the other manufacturer of also making their smartphone into a black, rounded rectangular slab with glass covering. The ironic thing is probably that any number of small changes to [Erich]’s project could likely have made the registered design not apply, such as through the addition of a colon between the hours and minutes, adding seconds, making the box into an oval, or changing the number of rotating elements.

Not all is lost

As [Erich] also notes in his blog post, there are still certain ‘fair use’ provisions with registered designs. Nobody is going to bust down the doors of a kindergarten when one of the preschoolers clumsily draws a Coca-Cola bottle without explicit permission from Coca-Cola’s lawyers. Similarly, anyone can in theory make their own copy of HS1982’s ClockClock24 clock so long as they do not sell it or otherwise make it publicly available.

This knowledge should give anyone who sets out to copy a design which they saw somewhere and liked at least some idea of how far they can take it. Publishing the project on a blog and making the design files available is the part where things can get dicey. Even making small alterations to the original design are not guaranteed to keep one from getting harassed by a company’s irate lawyers.

While there is a small chance of victory if [Erich] or someone else were to take a case like this to court, to argue that small-fry open-hardware projects are unlikely to harm the profits or sales of a company like HS1982, it would essentially be asking the law makers to add a major exception to patent law that would no doubt come with its own set of headaches.

In the meantime it seems that we can do little but get a chuckle out of the ClockClock24 clones available on Chinese stores for peanuts.

Recent Comments