A recent writeup by Tom Nardi about using the 6502-based NES to track satellites brought back memories of my senior project at Georgia Tech back in the early 80s. At our club station W4AQL, I had become interested in Amateur Radio satellites. It was quite a thrill to hear your signal returning from space, adjusting for Doppler as it speeds overhead, keeping the antennas pointed, all while carrying on a brief conversation with other Earth stations or copying spacecraft telemetry, usually in Morse code.

The Manual Way

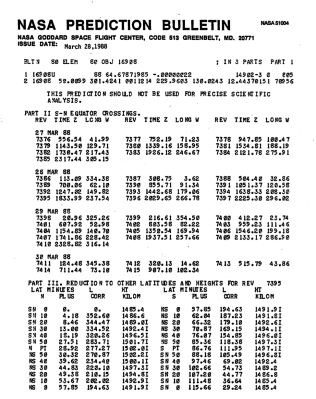

Pulling this off was quite a production in the pre-Internet days. To begin with, you needed data about each satellite’s orbit. This was obtained by signing up to a real-paper mailing list from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. An envelope arrived about twice a week by mail containing a stack of NASA Prediction Bulletins for the satellites you had requested. These contained the orbital parameters in what’s known as two-line element (TLE) set format, which you had to then type into your computer for processing. When we communicated with Space Shuttles, we would get the preliminary and later actual TLE data from someone within NASA by phone or FAX.

Unlike geostationary communications satellites, Amateur radio satellites are typically launched in polar orbits which take between 90 to 120 minutes to complete one revolution of the Earth. To communicate through one of these satellite, first we needed to know when a particular satellite would pass over Atlanta.

To solve this problem, I wrote a Fortran program on the campus mainframe computer, a CDC Cyber 74, a real computational beast of the day. This program propagated the state vector given by the TLE data, and generated a list of orbits which passed over Atlanta. These passes were characterized by the maximum elevation, the duration of the pass, the AOS and LOS (Acquisition / Loss of Signal) times, and the distance at closest approach. We humans would filter this list even further, ignoring passes that were very short or that occurred when we would be asleep or attending class — after all, the reason we were at GA Tech was to study hard, learn a lot, and graduate with a degree.

Object Orbital altitude Inclination Orbital period ====================== ================ =========== ============== Oscar 8 900 km circular 99 degrees 103 minutes Radio Sputnik 5,6,7,8 1600 km circular 83 degrees 120 minutes Space Shuttle STS-9 250 km circular 57 degrees 90 minutes Space Shuttle STS-51F 315 km circular 50 degrees 91 minutes

The satellites of the day had two popular modes. Mode A was easiest to use for most Hams, the uplink was in the 2 m band, and the downlink was on 10 m. Mode J also used a 2 m uplink, but the downlink was in the 70 cm band. A typical Ham satellite station would use a stationary horizontal loop antenna for 10 m reception. The 2 m and 70 cm antennas were usually Yagis, mounted on common rotatable elevation boom which was itself mounted on a vertical mast that could be rotated in azimuth. Ten meter reception was simple, no antenna movement required. Steering the Yagi antennas, however, was quite a task.

Having selected a suitable orbit, next we had make those Yagis follow the path of the satellite. In Amateur satellite stations, this is a completely open-loop process. You calculate where the satellite will be at a certain time, and drive the antennas to that point in space. If you remember the old home steerable TV antennas, before cable TV and streaming, the arrangement in a Ham shack is very similar. There is a rotator control box for each rotor, with an analog meter indicating direction, modern ones being digital, of course. These control boxes usually had three buttons for steering: Left, Right, and Brake release.

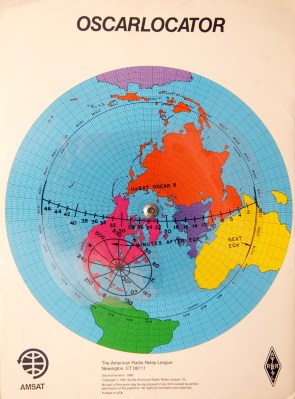

To follow the satellite, we had a couple of techniques available. One method used a graphical overlay of the satellite’s ground track and footprint on top of a polar projection map of the Earth. By rotating the ground track overlay to match the orbit’s position as given by the orbital parameter with the coolest name, Right Ascension of the Ascending Node, we could visually see the satellite’s path over our station. The ground path overlay has time tick marks, and the footprint overlay has azimuth lines and elevation rings. This crude graphical technique provides the basic information needed to track the satellite, within the broad beamwidth of our antennas. We also had to keep our clocks synchonized to WWV or WWVH — no Network Time Protocol back then.

A second technique was more precise, but required a trip across campus. Using another Fortran program, I could print a table of time, azimuth and elevation angles for a desired orbit. The operator wouldn’t have to interpolate angles from the graphical overlays: the numbers are clearly shown on the computer printout paper. Getting this data from the campus computer wasn’t trivial, however. Usually I would visit the computer center building across campus, login to my account at a terminal, and type in the data by hand. Upon execution, the program would generate a printout.

Then I had to wait at the output counter for the operator to separate and distribute the printouts to all of us impatient users. We felt so lucky when the club obtained a portable printing terminal with a built-in acoustic modem. This meant we could dial into the mainframe and run the programs remotely, and get our orbit schedules and tracking tables immediately without crossing campus — at the blazingly fast speed of 300 baud!

While all these machinactions were certainly within our grasp, it took quite a bit of effort and advance planning. And while a lone operator could communicate with a satellite, two people were better — one to operate the radios, the other to steer the antennas. I recall two events from this period which led me to consider a computer controlled project. First of all, we inherited two Commodore PET computers from one of the EE professors. Secondly, we had an ongoing issue controlling equipment up on the roof of the 5th floor from our shack located at basement level. There just weren’t enough wires to do all the things we wanted even for normal HF operations, much less satellite tracking.

Commodore PET to the Rescue

The Commodore PET computers we had were modified from their standard factory condition. They had full-size external keyboards, so you didn’t have to use the Chiclet keys. The internal memory had been upgraded to 32K RAM. My report from 1983 says this expansion memory card also had two general purpose 8-bit TTL output registers, which were used to talk to the outside world.

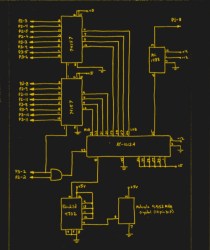

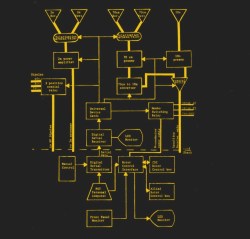

As shown in this diagram, the PET computer talks to two devices — the Rotor Control Interface selects and operates the rotor boxes, and the Digital Serial Transmitter, essentially just a UART that sent data serially to the roof to remotely control a variety of equipment. Rotor control was fun, because we only had one rotor control cable between the shack the the roof. I had to implement 8P3T switches out of relays and multiplexed the cable between rotors. This means that only one rotor could rotate at a time, but this wasn’t a severe constraint for our purpose.

Besides the rotator control signal multiplexing, there was quite a bit of auxilliary equipment on the roof which had to be remotely controlled. As shown in the diagram, we had RF coaxial relays to switch VHF/UHF antenna polarization, and to switch between 10 m and 70 cm downlink signal paths. In addition, there were preamps, down-converters, and power amplifiers which had to be turned on and off. Except for rotor multiplexing, most of these were static setups for the duration of a satellite pass, although the PET had full control of everything over this interface.  We made a UART interface connected to one of the PET’s TTL output registers to send this control data serially to the roof for control. I hand-drew all the schematics and hand-taped the PCB artwork – no KiCad back then.

We made a UART interface connected to one of the PET’s TTL output registers to send this control data serially to the roof for control. I hand-drew all the schematics and hand-taped the PCB artwork – no KiCad back then.

I very quickly identified a problem having the PET control of all this rooftop gear, which was not related to satellite operations at all. The PET wasn’t running 24/7, and it was slow to boot and load up from cassette tape. Operators who just needed to control relays on the roof for HF operations didn’t want to wait 10+ minutes to boot the PET. In fact they were quite vocal about it. So I added a manual control panel to bypass the PET. This philosophy has served me well over the years — computer control is great, but there are times when you need manual control, if only for testing.

We Don’t Need Closed Loops

There was still one problem with this setup — you might have noticed there is no feedback. There was a method for the PET to read signals, but despite trying a variety of methods we couldn’t get a stable enough feedback within our limited budget and limited mechanical skills. The azimuth rotor, which had an integrated feedback signal, would have been the easiest to monitor. But the elevation rotor we used didn’t have any such feedback.

We tried a long rod with a lead weight at the bottom, attached to a potentiometer. When the boom rotated up and down in elevation, the rod always pointed down. Good idea on paper, didn’t work so well in practice. We briefly played with synchromotors, which were really cool. Turn the shaft of one motor and the other motor across the room also turned the same amount, connected only by a few wires. But even these few wires were too many for our peculiar installation.

In the end, I concluded that for the satellites of interest and the antenna beamwidths involved, running the antenna rotation controls open loop was workable. To be sure, it caused a lot of headaches to procedurally check alighment before a pass, but once the pass began it worked as desired. I was continually tweaking the computer model of the antenna rotation, both the mathematical model and the constants such as dead-time, rotation speed, acceleration, etc. It was a crude solution, but it got the job done within our limited budget.

Aside: Zenith crossing and three axis mounts

You might think that a satellite passing directly overhead would be perfect — it is as close as possible to your station. Well, that’s not necessarily good. The problem is that when the satellite passes overhead, and the elevation angle approaches 90 degrees, the azimuth rotor will suddenly have to spin at an incredibly fast rate to keep pointed. There are ways to mitigate this — one method is to accept some pointing error and steer the antenna in a small circle around zenith — a circle whose diameter is determined by the speed of the satellite and the maximum speed of your rotor.

A more elegant solution, but mechanically complex, is to add a third axis of rotation. Two of the rotors are positioned before the satellite pass so that the antenna boom connected to the third rotor is perpendicular to the orbital plane. This way, only the third rotor is used during the satellite pass, and the other two rotors remain fixed.

Where is OSCAR?

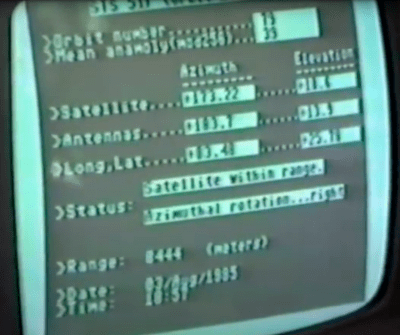

Providing the PET with interfaces to the real world was only half the battle. I still needed a way to calculate the satellite’s position. And while it was great to have a computer in the shack, the PET computer was thousands of times less powerful than the campus mainframe. There was no GUI, no tracking map of the Earth, just updating data fields on a text-based status screen.

I remember one major issue in the software development, however. There were several programs floating around the community those days for tracking satellites, and I hand typed one of the popular ones into the PET. I contacted the author of this program to let him know about my school project and get his permission.

But to my surprise, he replied “No, you can’t use my software”. Just a minor setback for a young college student who doesn’t know his limitations — I went to the GA Tech library, checked out a couple of books on orbital mechanics, and wrote my own algorithms. Surprisingly, the fundamental Keplerian laws and equations for orbital bodies aren’t that difficult to understand and calculate. Alas, when you solve for the antenna pointing angles to the satellite, it results in a transcendental equation. Solving that on the mainframe took milliseconds, but it painfully slow on the PET. Over a month or so that followed, I confined myself to programming at home all weekend, developed an life-long addiction to caffeine-laden diet colas, and emerged with a working program.

Upgrades

The manual controls for rooftop equipment were non-intuitive. You were literally toggling address and data bits into a UART. This could have been improved, of course, but a few of us began to question the original “no more wires can be routed to the roof” constraint. It turns out that it was indeed possible, with a bit of effort. A larger cable for signaling was pulled to the roof, and an improved interface panel was made. Furthermore, the PET was showing its age, too, so we upgraded to the Commodore C64 — with floppy disk storage. I made a new, smaller rotor control interface that connected to the C64’s user port and controlled the rotors by relays.

Successful Ops

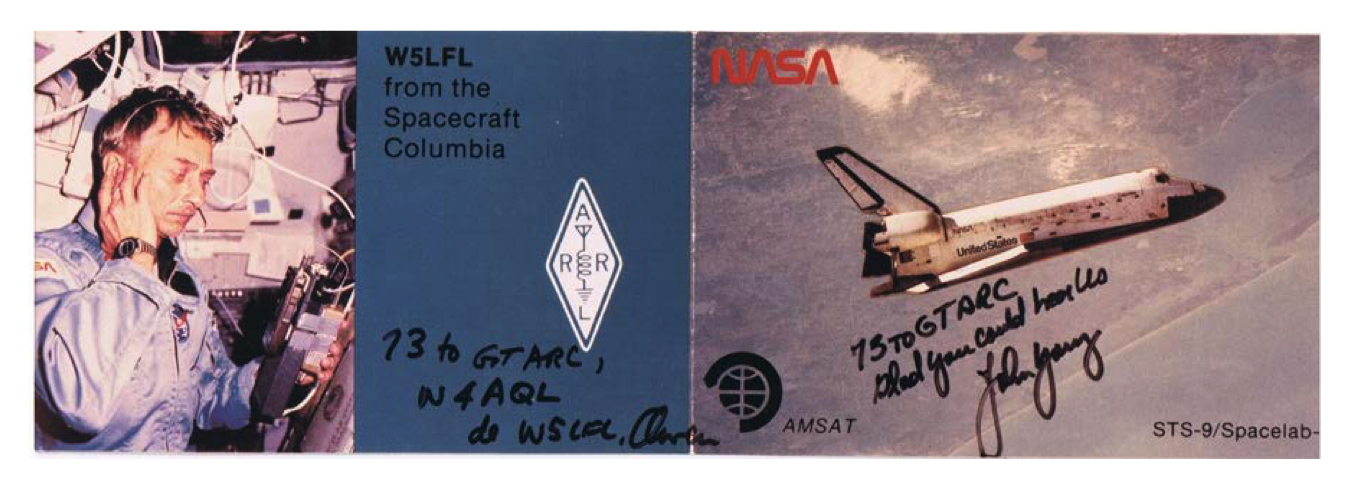

The system, while a bit finicky, did serve us well for a few years. Not only were we able to communicate over Amateur Radio satellites, but quite proudly we contacted the first two astronauts allowed to operate from the Space Shuttle under a new program called SAREX. In Nov 1983 Dr. Owen Garriott (W5LFL) heard us on Columbia’s STS-9 mission, which was piloted by our own GA Tech alumni Dr John Young. We were also proud of our own recent club alumni, Jim Worsham, W4KXY, who was on the team at Motorola that designed and built the custom radio used by Dr. Garriott.

Again in Aug 1985, we contacted Dr Tony England (W0ORE) on Challenger’s STS-51F Spacelab mission. Videos were made of these efforts, which you can see in the links below.

Future?

I challenged myself last year to build a miniature version of this project that fits in an Altoids can. It’s on the back burner for now, until I can track down a copy of the original software. Stay tuned…

Wrapping Up

After couple of years after I graduated, the company I worked with generously let me manufacture and market this C64-based tracking system under the unimaginitive name Satellite AutoTracker. That’s a story for another day.

I can’t overemphasize the impact this project had on me. The act of conversing with another radio station via a satellite pulls together so many engineering and science disciplines, from the physics of orbits and Doppler shifts to the minute details of learning to build PCBs to the overall system engineering efforts to make it all play together. Each one of these were interesting in and of themselves, but it was just plain awesome when it all successfully meshed together and worked.

I learned a lot building this project, but it didn’t seem like learning because it was so fun. That, folks, is the best way to learn.

Recent Comments